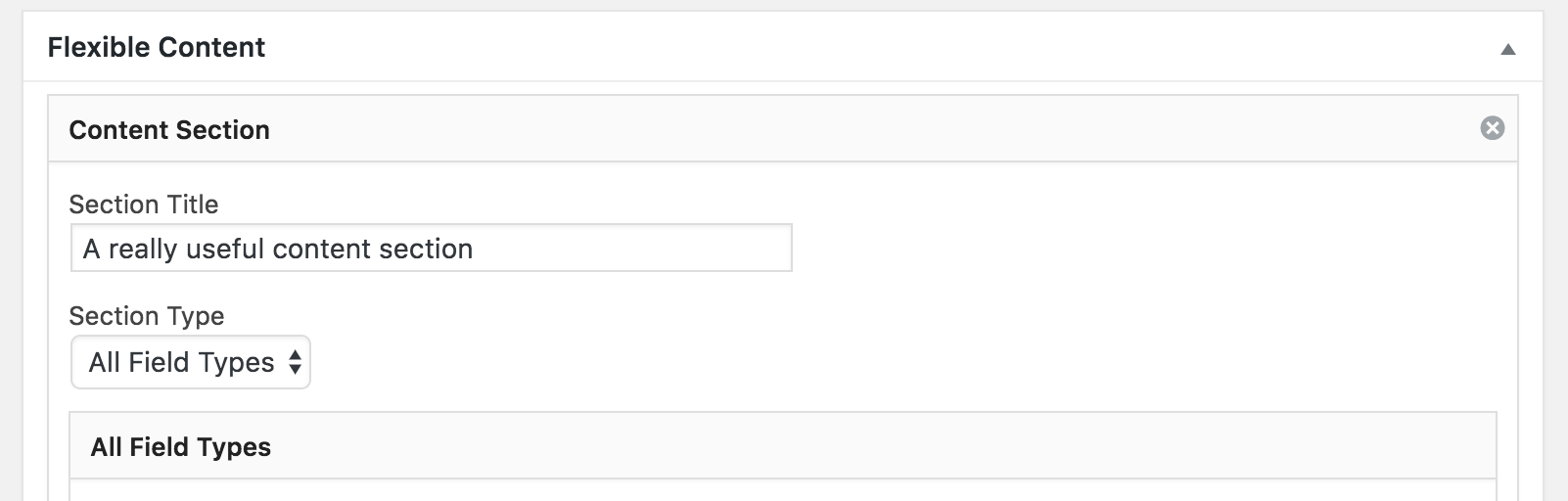

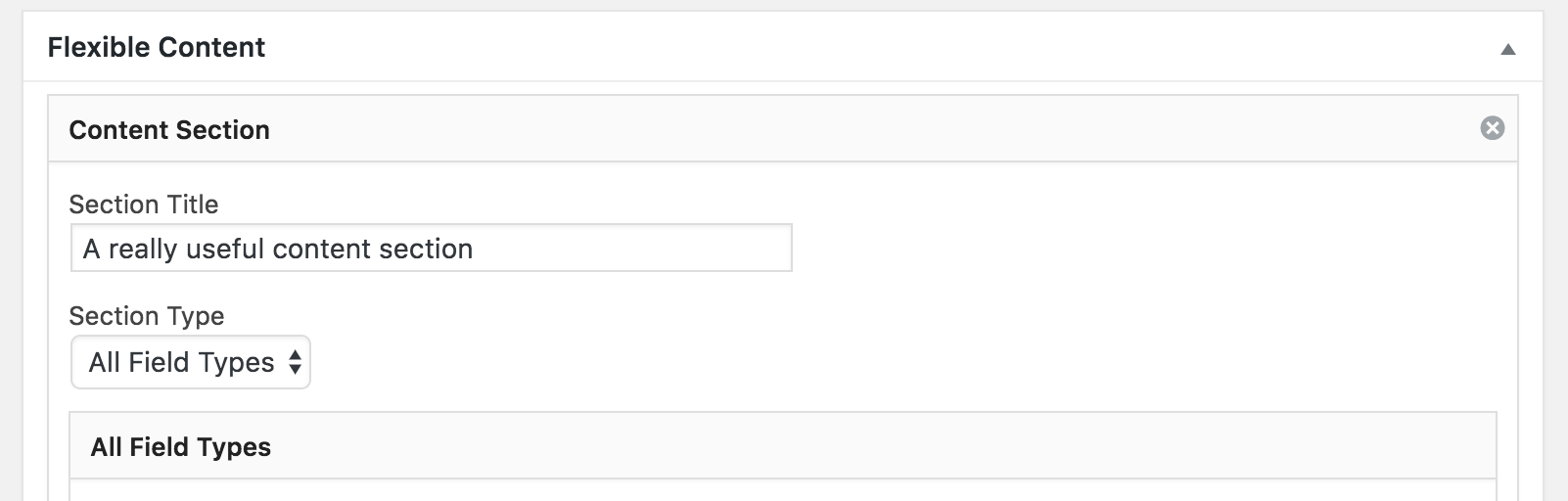

Flexible Content Fields in Field Manager

Field Manager doesn’t have a flexible content field type as Advanced Custom Fields Pro does, but it is possible to mimic the functionality by using a little logic.

Field Manager doesn’t have a flexible content field type as Advanced Custom Fields Pro does, but it is possible to mimic the functionality by using a little logic.

Enabling uploads of SVG files in WordPress is quite easy, and there is a tonne of posts on the Interwebs explaining how you do it. Usually along the lines of: function add_svg_to_upload_mimes( $upload_mimes ) { $upload_mimes['svg'] = 'image/svg+xml'; $upload_mimes['svgz'] = 'image/svg+xml'; return $upload_mimes; } add_filter( 'upload_mimes', 'add_svg_to_upload_mimes', 10, 1 ); And that’s pretty much it. Except it is not.

Uploading SVG files to WordPress when you’re behind the Sucuri CloudProxy Web Application Firewall isn’t that straightforward, but it is possible.

Running a real cronjob is much more reliable than WordPress’ built-in “maybe-will-trigger” solution. But if you’re running a multisite network, you have to add a crontab entry for every site you set up – which is tedious. Thanks to WP-CLI, we can use a small bash script instead, which will run all due events for all sites for us. Oh, and it works for single sites as well.

In your WordPress site, there are directories that include PHP files that visitors should never be able to access directly. They are only there for WordPress to function as an application that runs on your server. But because of WordPress’ directory and file structure, they are kind of accessible to the public. All of them are meant to be part of a larger application – WordPress, that is – and should not cause any harm if called directly – that we know. Some of the files execute some code even when ran standalone. An attacker might know of a clever way to make that code run in an unexpected manner, causing harm. To be on the safe side, we should deny access to all these PHP files from the outside world. Since we block access to them in our Nginx configuration, PHP will still run them as usual and WordPress will work just fine.

If you have a static IP address, like from your office, or your own private VPN, you can increase your security tremendously by restricting all logins to that IP address. The effect is that even if an attacker knows your login credentials, they will not be able to log in or access any part of the WordPress Dashboard.

WordPress requires write access to one directory, and that one directory only: the directory returned by wp_upload_dir(). By default, this is /wp-content/upload, but it can be configured to anything that is beneath your document root, like /media, if you want to.

If you’re using a strong password, brute-forcing is a very inefficient way of breaking into your WordPress account, and if it is really strong, dictionary attacks won’t help much either. However, there are are other, easier, ways for a mischievous person to get their hands on your login credentials e.g. with phishing, keyloggers or a MITM attack. By using a two-factor solution, you will increase your login security by an order of magnitude.

To be honest, I don’t exactly know too much about Big-IP, but I’ve come across someone who use it. They terminate HTTPS in Big-IP and WordPress runs on plain HTTP on port 80 on the backend nodes. By default, this makes WordPress confused, so you can’t login to the WordPress dashboard.

Fail2ban works by filtering a log file with a regular expression triggering a ban action if the condition is met. After a preset time, it will trigger an unban action. Without much effort, we can have WordPress log all authentication events and have fail2ban react on them.